This is a common question we get asked in Strengths Model Case Management. So, how does the model approach the concept of motivation?

You can’t motivate people. So, stop it. I know that sounds a little harsh. I’m only saying this because it will spare you countless hours (days? months?) of frustration and emotional exhaustion. So, what, just sit back and let people do what they want? I didn’t say that (you really are frustrated). The point I am making is motivation is a complex phenomenon. So, there isn’t a simple trick to motivate people to do something.

Yes, we can coerce people to do things (you better do this or I’ll…) So yes, coercion is a simple trick to motivate people to perform a short-term behavior, but that’s not why we are asking this question, right? Typically, this question of “How do I motivate people …?” arises because we sincerely want to do something that will help a person take steps that will bring about long-term change or improvement. So, let’s look at a few things we CAN do.

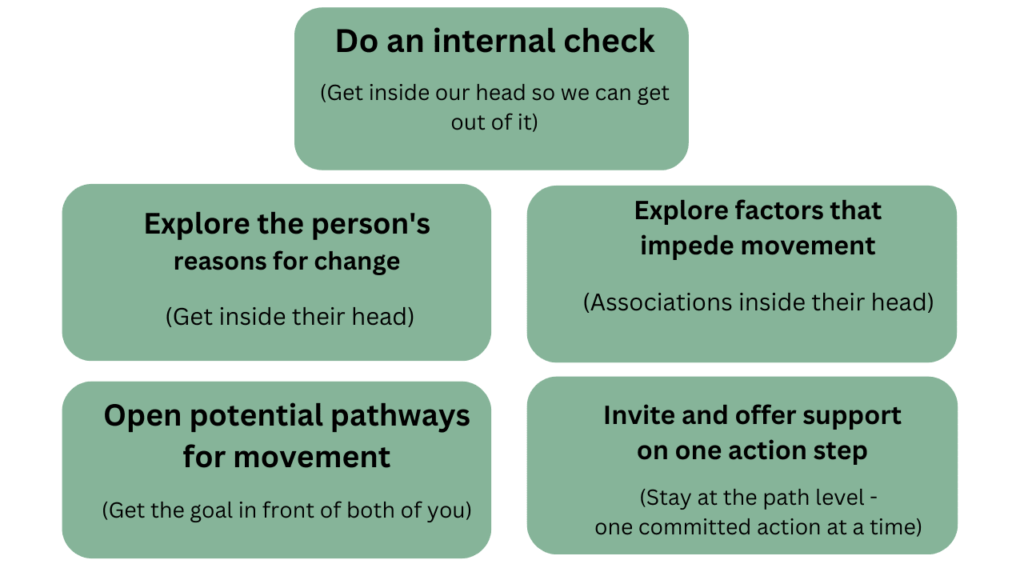

Do a quick internal check

A good place to start is always with ourselves. Why DO we want this person to do something? Many times, it comes from a place of best intentions. We care about the person, we want them to succeed, and we want them to do well in life. Sometimes, it is out of concern. We worry about the person and the potential consequences that might occur if they don’t do something. Other times, it is out of frustration. We think of the potential pressures or burdens on us that might result if they don’t do something.

Whatever the reason, our internal affect feels unpleasant at the thought of the person not doing something. The thought of them doing the thing we would like them to do would bring about a more pleasant affect. We would feel better about it, or at least a little less yucky than we feel now.

Being aware of our reasons for something AND our internal affect is an excellent way to keep us grounded. The key is to do this without judgment on ourselves. Just notice it and accept it. Don’t evaluate it. Don’t try to rationalize it. It’s just how you feel. Ok, so now I just sit there and accept how feel and just let the person do what they want? Not exactly. However, if we can get ourselves grounded enough to get outside of our own heads for a bit, we give ourselves an opportunity to get curious about other things that impact motivation. You will need to keep channeling your internal zen-like state, though, or you will just get pulled back into your own head.

Explore the other person’s reasons for change

So, you know you want the person to do something, but why would THEY want to do it? Because they said they want to! Okay, but WHY do they want to do it? Big difference. This is where we must dig a little deeper with people because, frequently, they may not have really thought about why they want to do something. This is where it can get a little complex.

For starters, sometimes people want to do something because they want to move toward something (e.g., I want to get my own place, I want to get a job, I want to meet other people, etc.). Sometimes, though, it is because they want to move away from something (e.g., I hate it here, I don’t want to get in trouble, I want people to quit bugging me, etc.). Any of these reasons can spur movement; however, when our movement is prompted by a desire to move toward something, it has a greater likelihood of leading toward sustained momentum. When our motivation is prompted by movement away from something, we may lose momentum when the particular stressor is no longer present. Of course, people can have reasons that are embedded in both a desire to move toward and move away from something.

Another area to explore is where the drive to do something is coming from. For some people, they may be focused on a desired external reward. For example, “Doing this would allow me to have ____ so I can ____” or “If I do this, I will be able to ____.”This is called extrinsic motivation. Other times, people may want to do something because of the internal value that is connected to it. For example, “I enjoy being connected to other people,” “Taking care of my family is important to me,” or “I value doing things that give me purpose.” This is called intrinsic motivation.

Both types of motivation can serve a purpose. Sometimes, we may not get much enjoyment from everything we have to do along the way to reach a goal, but if the reward (extrinsic motivation) is important enough to us, it helps us get through some of the mundane stuff. For example, a person might feel stressed filling out job applications; however, the importance of being seen as a capable provider and being able to engage in activities with their family might get them through the discomfort of completing the application.

Now, this is a super simplistic overview of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. The main point here is being curious enough about a person to explore what extrinsic and intrinsic factors might be driving their desire to do anything. Without ANY extrinsic or intrinsic motivators being present for the person, it is difficult to get any movement. Also, listen for “should” statements. This is where we think we should do something. However, it is driven by other people’s expectations of us or how we perceive others may view us.

Be patient with people because they may not have thought about why they want to do anything or where it comes from. Exploring this is fruitful, though, because it gets us out of our heads and into theirs. As you can probably guess, having intrinsic motivations is key to longer-term sustained movement. Sometimes, reaching an extrinsic reward we are looking for may take a while, and we can start to feel defeated. With intrinsic motivation, each step is something we do because it is aligned with our values, not solely because of the external reward.

Key practice note: If we are going to have conversations with people about why they might do something, we can’t be overly invested in the final outcome. People will be more open to talking about their reasons for change (or not changing) if they feel we are sincerely trying to understand their ambivalence rather than pushing them in a particular direction. Think motivational interviewing.

Okay, I have successfully let go of ownership of a specific outcome and elicited some great extrinsic and intrinsic motivators for why this person likes to do something. Can we now just start doing it? Slow down, speed racer. You have done some tremendous foundational work; however, we need to explore one additional area before we sprint out of the gates.

Explore the factors that impede movement.

When somebody asks the question, “How do I motivate someone?” it typically means that there is ambivalence lurking in the background. If someone has no extrinsic or intrinsic motivators, they hold for accomplishing something, then that would suggest a person is in the Stage of Change called pre-contemplation (or not seeing any reasons to do something or make a change). For now, we are going to assume that the person actually does have reasons for doing the thing we would love to “motivate” them to do.

If this is true, then we need to understand more about what makes movement challenging for the person. It could be a wide range of things, so I’ll just give you a few common ones: fear, self-doubt, worry, lack of faith, feeling overwhelmed, not knowing where to start, embarrassment, self-judgment, self-consciousness, etc. You get the picture. Remember earlier when I said we need to do an internal check on OUR effect? Well, the people we work with experience affect as well (no way! – Yup).

And sometimes, when we start thinking about even a tiny step toward a goal we want, we can feel unpleasant affect. And when we feel unpleasant affect, we attach an emotion label to it (I’m nervous, scared, overwhelmed, etc.). And then, to top it off, we add a cognitive evaluation (I can’t do that, I’m going to look stupid doing that, this isn’t going to make a difference anyway, etc.). Now, we have the perfect recipe for stagnation.

You see, brains don’t especially like change. They like routine and predictability. It’s why our brains are adept at helping us form habits. This can be super helpful at times because we can go on autopilot through a lot of daily minutiae and not get bogged down by overthinking every tiny movement involved in a complex activity (like making a pot of coffee, driving your car to work, turning on the TV, etc.). Of course, not all understood behaviors are helpful and useful. We all experience unpleasant affect. And our typical go-to response is to try to make it go away as fast as possible.

For example, you start feeling anxious (unpleasant affect) when you think about taking a particular step, so you find a way to get out of it and maybe do something else that brings pleasant affect. Or you start feeling overwhelmed (unpleasant affect) when you think about taking a particular step, so perhaps you shut down entirely and decide to give up on the goal altogether.

Since we will frequently encounter things that elicit unpleasant affect, we get lots of practice responding to it. And when we practice avoidance responses over and over, we have, Voilà, a perfectly designed learned behavioral response loop to get our brains back to routine and predictability.

Yeah, but if the person just pushed through the discomfort and kept taking steps toward their valued goal, wouldn’t they eventually get to a place that brings more pleasant affect than what they feel right now? Perhaps, but you see, brains don’t care about any particular life goals. They have a straightforward job to do, and that is to constantly monitor our internal and external environments (drawing on learned associations from past experiences) to make predictions on what is occurring and the best possible response.

We are all wired differently because we have all had diverse experiences throughout our lives (pleasant and unpleasant). Therefore, our brains have had a lot of practice experiencing, predicting, and learning to respond. So, if we want to support people with the logistical (taking the step), we must spend some time exploring the person’s internal response to the step. A logistical step might appear fairly simple to us (Just do it), but for that person, an internal battle to avoid discomfort and quickly get back to regular brain programming might be occurring. Even if regular programming is also unpleasant. Remember, brains don’t particularly like change.

Open potential pathways for movement

Now, here is the good news. While brains don’t like change, they can. That’s called neuroplasticity. If we want to support people during change (or thinking about change), there are some helpful things we can do during the transition.

• Acknowledge and validate the discomfort a person feels.

Discomfort can make a lot of internal noise. And when we try to avoid it or fight with it, it sometimes can get noisier. You know, just like a pesky little two-year-old who is annoying you. You try your hardest to ignore them, and wouldn’t you know it, they just get louder and louder. Well, maybe that was just me as a kid. The point is discomfort has a way of making itself heard, so allow it to have its say. When we acknowledge and validate something (if done with sincere empathy), we form an environment where the brain is at least willing to consider a change.

• Bring to the forefront the person’s reasons for wanting to do something.

If the brain is willing to relax its internal alarm system, then we have an opportunity to see what else is inside there. Here is where we draw to the forefront those specific reasons for change we discussed earlier. And the closer we can stick to their words, the better. Why? Brains like the sound of their inner voice. And if they hear words that closely resonate with their own deeply held values, then they are more likely to continue the conversation.

• Extend an invitation to explore.

If a person still seems hesitant to take a step toward action, a safe transition is to invite a person to explore possibilities or options. Would it be helpful if we just looked at a few options you might consider? Would it be helpful if we gathered some more information about _____ before you decide what to do? Would it be helpful if we looked at what it might take to do that? Would it be helpful to talk about what support you might need to do that?

• Consider using a tool like the Personal Empowerment Plan.

While talking about goals and possibilities can be fruitful, using something visual and structured can help bring the pursuit of a goal into a more focused, intentional commitment to act. When a goal remains a thought inside a brain, it can get entangled with all the other thoughts, emotions, and narratives that have taken up residence inside there. The goal becomes like that sock you periodically see in the window of a washing machine as it spins around with all the other clothes.

The Personal Empowerment Plan is a vehicle to create some space between the goal (as well as its meaning and importance) and all the other things we have going on in our lives. Yes, we may still feel overwhelmed and have worries, doubts, or fears related to the goal. However, with the goal now in visual form, we have a vehicle to bring focus to our next “best step” to move toward that goal. And with each step accomplished, no matter how small it is, we see that we can mindfully move toward something even amid life’s challenges. The PEP allows us to objectively see movement and progress. And when a challenge crosses its path, we see ourselves take a step to address it or find an alternate route (while still making movement toward the goal). We are building muscle memory for empowerment. Remember, brains like routine.

• Offer practical ways you could support a person around specific steps.

While you want to support a person to take as many steps as they can on their own or with help from their existing natural supports, you should be prepared to talk with the person about any practical things you can do related to specific steps along the way. A lot will depend on your role within the organization and the types of support you are able to offer. Using a Personal Empowerment Plan can help with these key decision points. When discussing a particular step, we have the opportunity to refine a step into its most simple, actionable terms (Go to, call, text, write, ask, etc.). We also have the opportunity to assess what the person is able to do and what support might be needed.

Awesome! So, I just go through all these steps with people, and they will be motivated and self-directed enough to take on any goal. I wish it were that simple. What I hope we have accomplished here is two-fold: 1) the recognition that motivation is complex, and 2) the recognition that there are things we can do that increase the likelihood of positioning ourselves to be in support of a person’s desire to move toward something (versus remain stuck in our own frustration around a person’s lack of movement).

Let’s recap some key points:

Working with people is never a linear approach. A person can take a step and then jump right back in their heads (worries, doubts, fears, etc.). And then we, as workers, can jump back into our heads (frustrated, overwhelmed, skeptical, hopeless, etc.). Sometimes pauses, misstarts, barriers, obstacles are opportunities to work through difficulties. Reassess what is occurring internally, having compassion on ourselves, remembering the reasons for change, and returning to the path level (the step in front of us) and looking at it together. What are the options? What are alternative paths? Is there additional support needed? Is there a smaller step?

Motivation isn’t just a burst of energy we experience that pushes us into action. Motivation is something we build by taking action, even in its smallest increment of movement. Motivation isn’t an excitement we experience about every step we take. Motivation is experienced when we recognize we have agency to do something even amid challenges or even mundane steps.

Neurons that fire together, wire together. Each time we take a step toward something we value or want in our lives, we reinforce a narrative of what we can do (versus what we can’t do). Motivation isn’t just about the end goal. Motivation is about our own attention to and celebration of effort and movement, and building, rebuilding, or restoring our sense of self.