Strengths Model Case Management was developed in the mid-1980s with a specific purpose in mind – to help people make movement toward things they value or want in life, even amid problems, barriers, or challenges they might experience. When the Strengths Model was initially developed, this was a significant paradigm shift in mental health services at the time. Traditional case management approaches often focused on diagnosis and symptoms, held low expectations for what people with mental illnesses could achieve in their lives, and frequently used stabilization and maintenance as measures of success.

The Strengths Model arose in response to this, viewing people not only as capable and possessing a unique array of personal and environmental strengths but also challenging and equipping staff to focus their efforts and support toward helping people achieve life goals and roles that anyone else in the community might pursue.

Over four decades of research have shown Strengths Model Case Management to be effective. Eighteen studies have tested the effectiveness of the Strengths Model with people who have serious mental illnesses (Mendenhall, Grube, and Jung, 2024; Dissanayake et al., 2023; Nagayama, Tanaka, & Oe, 2023; Roebuck et al., 2022; Latimer et al., 2022; Soulantika, 2021; Gelkopf et al., 2016; Tsoi et al., 2016; Fukui et al., 2012; Barry et al., 2003; Stanard, 1999; Macias et al., 1997; Macias et al., 1994; Ryan, Sherman, and Judd, 1994; Kisthardt, 1993; Rapp & Wintersteen, 1989; Modrcin et al., 1988; Rapp and Chamberlain, 1985).

These studies have collectively produced positive outcomes in the areas of psychiatric hospitalization, housing, employment, reduced symptoms, working alliance, hope, quality of life, functional improvement, leisure time, enhanced skills for successful community living, social and family support, and decreased social isolation.

While the research base on Strengths Model Case Management has primarily focused on adults diagnosed with a serious mental illness, the model has also been effective in working with a variety of other populations, including unhoused individuals and families, transitional-aged youth (ages 16–25), youth with severe emotional disorders (12–16), older adults (65+), individuals with co-occurring substance use disorders, and individuals who have experienced domestic violence, sexual assault, or human trafficking.

The success of the Strengths Model across diverse populations, settings, and cultures is due to its humanistic approach of looking at the whole person (not just what brought the person into services) and the uniqueness of each person’s values, aspirations, capabilities, and what has been useful or helpful in their life.

Strengths Model Case Management encompasses both a framework of practice and a set of tools, methods, and interventions to more effectively engage with the people we work with AND support them in making movement toward what they value and want in life. Below, we will guide you through the basic conceptual framework of Strengths Model practice and briefly show you how the tools, methods, and interventions fit into that framework.

Keep in mind that the framework is only intended to help us visualize the pathway on which we want our work with the person to progress. Rarely is our work with people linear. The framework allows us to think reflectively about where we are at with a person, where we want to get to next, and what might be preventing movement forward. Here, we can ground ourselves in the present moment based on where the client is at – not where we think they “should” be.

The framework also helps us from getting caught up in a reactionary style of case management, responding merely to the “problem of the day” or trying to quickly fix things that are distressing, uncomfortable, or problematic for the client. While the Strengths Model doesn’t ask us to ignore or be unresponsive to problems or challenges that clients experience, the Strengths Model is about being purposeful and intentional in the work we do with people so we can ultimately help people better navigate the problems and challenges they do face in their lives.

Starting with the Challenges

The goal of Strengths Model Case Management is two-fold:

1: To help people make movement toward a life that encompasses what they value and want in life.

2: To increase people’s ability to exercise their power related to how they view themselves and how they interact with their environment.

Sound simple? It could be if that is what brought a person into services. Rarely do people show up for their initial intake, saying, “I came here today because I have this meaningful and important goal that I would like to achieve, and I would like some help. I want to learn how to better respond to ____, so I can achieve this goal.” This does not mean that people who come to us seeking help do not have goals. Instead, it is merely to point out that what typically brings people into our services are the problems or challenges they face.

While we hope to do more in Strengths Model Case Management than just helping people overcome immediate problems or challenges, for the model to be effective, we have to “start where the person is.” By the time a person comes into our services, they have often faced a myriad of life challenges. Figure 1. lists a few of the possible life challenges that people may have faced (or are currently facing).

Figure 1. External Life Challenges

People can face a myriad of challenges in their life. Many of these challenges occur in the environment surrounding the person. For some people, these challenges have occurred throughout their life. Many people we work with may have experienced or are currently experiencing several or all of the challenges listed in Figure 1.

Since Figure 1 is not an exhaustive list, you could probably name several additional external life challenges people face. When people experience any of these things in childhood or adolescence, they are called adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Multiple studies have demonstrated the relationship between ACEs and a wide range of mental health problems. People diagnosed with serious mental illnesses experience an even higher rate of exposure to ACEs. Research on adverse experiences in adulthood continues to show a strong association with poor mental health, physical health, quality of life, social functioning, and recovery (Stumbo et al., 2016).

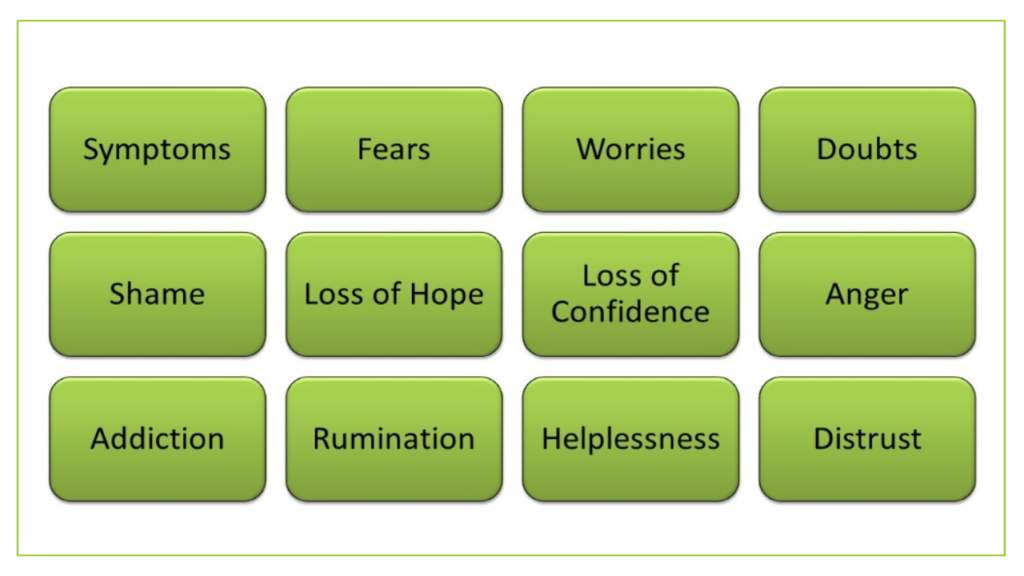

In addition to the life challenges that people may experience externally, people also experience a wide range of internal challenges. Figure 2. lists a few of these possible challenges.

Figure 2. Internal Life Challenges

People can experience a wide range of internal thoughts, feelings, or emotions that are distressing, uncomfortable, or problematic for the person. This could include symptoms such as anxiety, depression, racing thoughts, psychosis, etc. It could also include fears, worries, or doubts about the future. Or rumination on past losses, trauma, decisions made, or negative messages about oneself that have become internalized.

The life challenges in Figure 1 and Figure 2 often have a reciprocal effect on each other. What we experience externally can influence how we interpret internal experiences, and what we experience internally can influence how we interpret what we experience externally. This applies not only to the people we serve but also to all of us as humans.

This is an important recognition in Strengths Model practice. Biologically and physiologically, there is little that separates any of us from the people that we serve. This does not mean we all have the same experiences, resources, opportunities, privileges, supports, connections, physical capabilities, or environmental surroundings. It just means that we share a commonality in that our minds and bodies can be affected by the reciprocal effect of what we experience externally and internally.

The importance of understanding this is to allow ourselves to have compassion for others when a person is continuously responding to a host of internal and external stimuli that can be unpleasant, distressing, uncomfortable, or overwhelming. While each person’s response to these types of things can be different, many people’s responses to these stimuli are to control or avoid. Our mind’s capacity to absorb a bombardment of internal and external stimuli has limitations. So, we have to choose what we pay attention to selectively. This in and of itself is not a bad thing. Few people enjoy feeling stress, ruminating on painful thoughts, feeling anxious, or being distressed about something.

Many of us have employed distraction techniques to temporarily avoid something painful, stressful, or uncomfortable. This can be an effective short-term strategy. We must also be aware of potential pitfalls to using distraction as a long-term strategy. For one, we may not attend to things that increase stressors in our lives. Another pitfall is that these distraction techniques can eventually lose efficacy and increase the likelihood and intensity of intrusive thoughts or images. Finally, we can spend so much time trying to control or avoid uncomfortable thoughts, emotions, or symptoms that we stop taking steps toward things we value or want in life.

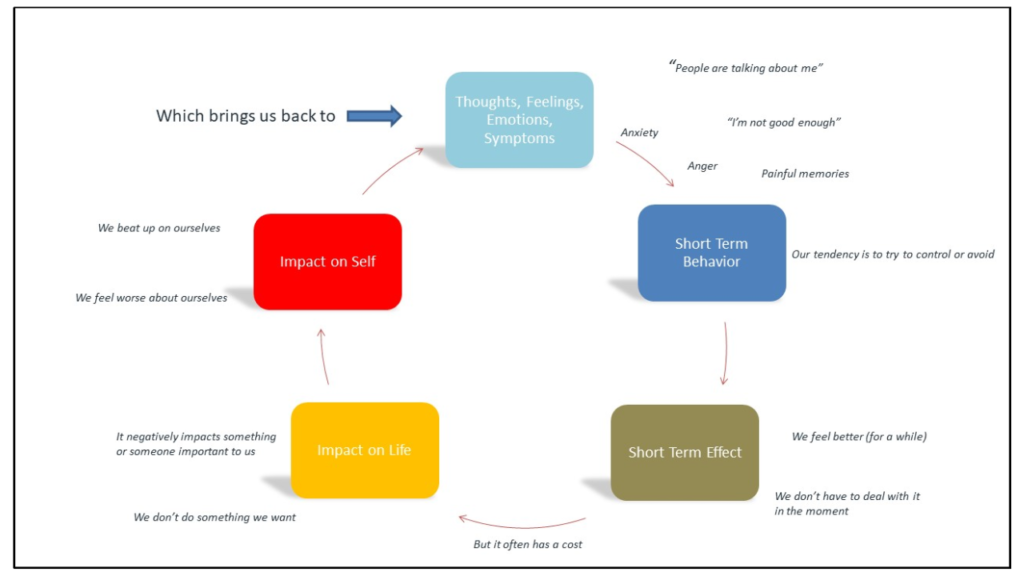

Here, we find our responses to unpleasant, distressing, uncomfortable, or overwhelming external and internal stimuli become highly problematic in our lives. We become caught up in the battle to control unwanted thoughts, feelings, and emotions and stop taking steps toward things that we value and want in life. Instead of making progress toward something that might improve our quality of life or well-being, we find ourselves in an unhelpful loop. Figure 3 shows this problematic loop.

Figure 3. The Unhelpful Loop

In the diagram above, we start at the top with uncomfortable thoughts, feelings, emotions, or symptoms that a person might experience. Symptoms could include things like anxiety, depression, racing thoughts, hearing voices, etc. A person could feel agitated, worried, stressed, overwhelmed, etc.

A person could also be ruminating on painful memories like losses or past traumas. A person could also be internally repeating judgmental messages to themselves like “I’m not good enough,” “I ruin everything,” “People are talking about me,” “I’m damaged,” or “bad things always happen to me.” As we mentioned earlier, a common approach to dealing with things we experience that are uncomfortable, painful, distressing, or overwhelming is to try to control or avoid these things. We may engage in short-term behaviors in an attempt to avoid what we experience.

While some short-term behaviors may be just a temporary and helpful distraction, a few of the more potentially problematic behaviors could include the use of drugs or alcohol, binge eating, excessive spending, excessive sleeping, isolating from others, avoiding anything unpleasant, beating up on ourselves, getting angry with others, or giving up. These short-term behaviors can be reinforced because they often have a short-term effect. We may feel better for a while, or we don’t have to deal with something in the moment.

These behaviors can also potentially have a cost. They could impact our lives by keeping us from doing something that we value or that is important to us. Or the behaviors could negatively impact valued areas of our life (housing, employment, education, community involvement, etc.) or people important to us. This, in turn, can impact how we view ourselves. We might feel shame, blame, self-judgment, or invite other negative self-narratives. All of this leads us back to thoughts, feelings, emotions, or symptoms that we initially found distressing or uncomfortable.

This is why we call this an unhelpful loop. Rather than leading us in a direction toward what we value or want in life, we spend a considerable amount of time trying to find ways to avoid or control the discomfort. Unfortunately, we find ourselves in an unwinnable battle because we can’t find a way to completely control or avoid what we are experiencing internally or externally. For some people, this can go on for years and years. And even when there seem to be periods of respite, there can be the continual pull to return to the unhelpful loop.

This phenomenon is not something that only happens to the people we serve. It can occur with any of us. We have all experienced the unhelpful loop at various times in our lives. Have you ever procrastinated around something difficult or challenging for you to do? Or messed up dinner? Or turned down an invitation to do something fun because it felt outside your social comfort zone?

These are often benign examples that can sometimes lead into an unhelpful loop. The unhelpful loop becomes problematic when we find ourselves entirely or continuously exiting the road that leads us toward what we value or want in life. For example, the person who starts to view themselves as incapable avoids anything difficult or uncomfortable.

Or they stop doing things they enjoy (like cooking) because they worry they will mess it up. Or decides to completely isolate because of fear of being around other people or discomfort with the unknown. It is even more detrimental when the person begins to attribute what is occurring to there being something wrong with them or they view themselves as damaged or broken. Some people will start to define themselves and their lives through the lens of their symptoms. Some people will see their identity AS their diagnosis.

Enter Strengths Model Case Management

Strengths Model Case Management was developed to help people make movement toward things they value or want in life, even amid problems, barriers, or challenges they might experience in their lives. Strengths Model Case Management is intended to help people see that they are more than what they think, feel, or experience. We can conceptualize Strengths Model Case Management as encompassing five primary phases, with each phase having multiple core processes (approaches and interventions) that help the worker and person receiving services move from one phase to the next.

Table 1. Five Primary Phases of SMCM and Related Core Processes

| Phase of SMCM | Core Processes |

| Engagement | – Use of empathic communication – Providing tangible support – Employing noticing behaviors |

| Invitation to Explore | – Finding a context to introduce the Strengths Assessment – Identifying fundamental values, desires, and aspirations – Identifying key capabilities – Identifying environmental strengths that are useful or helpful – Exploring possibilities related to a goal or value |

| Invitation to Act | – Finding a context to introduce the Personal Empowerment Plan – Taking committed action through a small, measurable step – Celebrating movement and reinforcing capabilities – Recalibrating the approach, when needed, based on learning – Negotiating the role of support related to the goal |

| Establishing and Strengthening Anchors | – Solidifying gains by returning to the Strengths Assessment to reflect progress and capabilities – Enhancing awareness of the “active ingredients” related to various personal and environmental strengths – Reinforcing areas of personal empowerment |

| Graduated disengagement | – Consolidating learning related to areas of movement during time in services – Focus on targeted areas where additional support is needed – Making connections to less intensive or appropriate follow-up support when needed |

Let’s take a look at these five primary phases further.

Phase 1: Engagement

While we call the first phase of SMCM engagement, the reality is that we are continuously engaging, building the relationship, and strengthening the working alliance throughout the helping process. That being said, our first few sessions with people are critical in laying the foundations for future work together.

While all case management models begin with some type of engagement phase, the various specified approaches and interventions within a specific model of case management can be the difference between purposeful engagement that moves us in a direction that increases our likelihood of being effective versus a reactive approach to engagement which can perpetuate an unhelpful loop a person experiences.

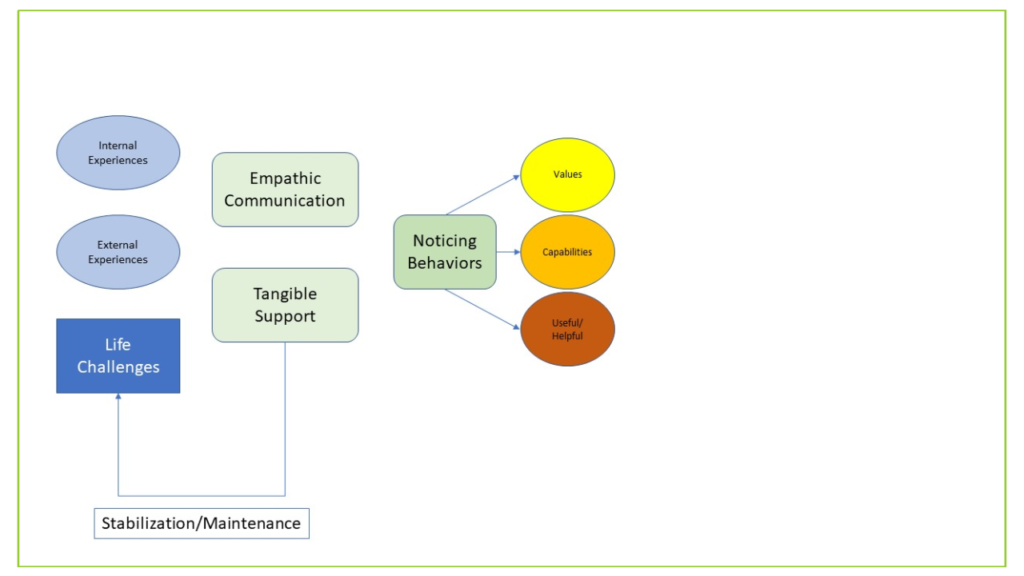

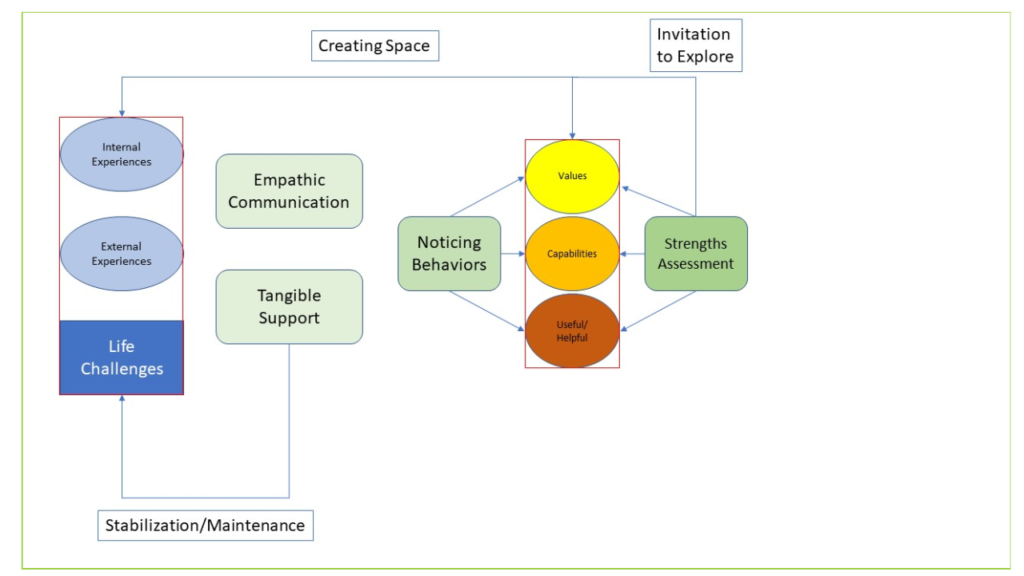

Figure 4. Phase 1: Engagement

As you see in Figure 4, we recognize that when most people come into contact with our services, it is typically a result of the internal or external life challenges they are experiencing. Our initial contact with a person can be a time when the person is experiencing a heightened amount of distress or being overwhelmed in life. The way the person is responding to the internal or external challenges they are experiencing can also have an impact on the worker.

The worker needs to stay grounded and focused on the three core processes that can be used to validate and understand a person’s experiences (empathic communication), provide help related to a person’s immediate challenges (tangible supports), and be observant of key values/desires/aspirations, capabilities, and useful or helpful environmental strengths that exist even amid the person’s life challenges (employing noticing behaviors).

It is critical that all three of these core processes are used during the beginning of the helping process. All case management models offer people tangible support to help address immediate needs when they first come into services. Often, tangible support is based on some type of assessment of need related to a person’s immediate life challenge (e.g., connection to resources related to housing/shelter, income, mental or physical health symptoms, substance use, transportation, immigration, legal, etc.). The goal of providing these tangible supports is often geared toward helping people achieve immediate stability and then maintain that stability. This might be enough case management support for short-term programs that work primarily with people who are self-directed and require low levels of support.

Unfortunately, this approach to case management is the one embedded in most programs nationally and internationally, regardless of the level of need of its service recipients. It is also the one case management approach that produces the poorest outcomes, especially when working with people with moderate to severe mental health symptoms, addiction, or complex trauma. When used with these populations, this approach to case management can perpetuate the unhelpful loops discussed earlier.

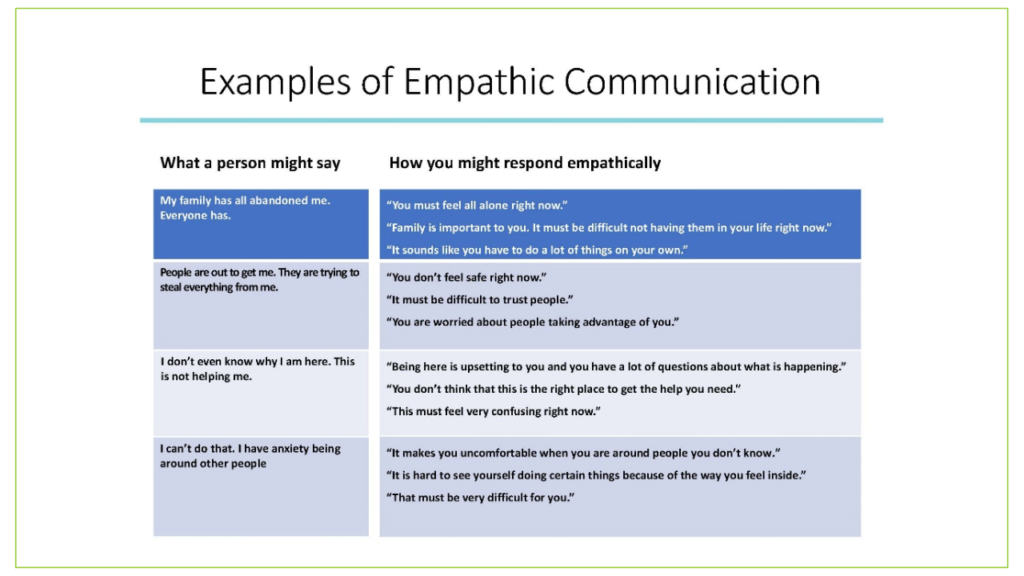

Incorporating empathic communication, noticing behaviors, along with tangible supports helps differentiate SMCM from many other approaches to case management during the engagement phase. Empathic communication is an active effort to understand another person’s frame of reference. It is about going beyond just the words that people use and listening attentively to understand the core meaning underneath a person’s words and the emotions and thoughts they may be experiencing. Figure 5 shows a few examples of empathic communication.

The first column has an example of what a person might say. The second column uses a statement that is a best attempt to understand the meaning behind the person’s words and any associated emotions. As you will see in the phrases in the column on the right, there are a multitude of potential responses (we only show three as examples). This is because our response is only our best guess at what a person might be experiencing. It’s an invitation to the other person to confirm, clarify, revise, or even offer back something completely different. When approached with a sincere desire to understand, it creates the potential for further engagement.

Figure 5. Examples of Empathic Communication

Empathic communication is not just a collection of pithy statements we use to placate people. Empathic communication is authentically listening to people with our entire being, including our eyes, ears, and our heart. It’s more about us actively listening than talking and requires us to be fully present, grounded, and aware of our own implicit biases and potential triggers based on our own past experiences. Empathic communication,

when used intentionally and without judgment, can contribute to developing the working alliance because it helps people feel they have been heard and are in the right place for support. Empathic communication can help reduce judgment, shame, and blame from a person’s experiences. We can use it to help people normalize their internal response to something and even understand the purpose or utility of a particular response or behavior employed by the person.

Empathic communication is also a pragmatic approach to keep us grounded and less likely to be immediately drawn into a reactive mode of service delivery. When we respond to the emotional experience of the person we are working with…rather than their just their words, behaviors, or our own internal reactions……we are always in a better position to understand, connect, and be effective.

The use of good empathic communication also helps us to employ our noticing behaviors more effectively. Here, we are not talking about us noticing other people’s behaviors, but rather our behavior as workers in being able to notice other realities that might be present, in addition to just the presenting problem or challenge the person faces.

Table 2 shows some examples of specific areas where we are trying to be mindful to notice things for the purposes of SMCM. Later on, we might record some of these things on a Strengths Assessment, but early on in engagement, our only job is to notice them.

Table 2: Examples of Specific Areas to Employ Noticing Behaviors

| Areas | Examples |

| Values | – Family is important to me – I like being able to help others – I am able to express myself through my art – I feel more like myself when I’m connected to nature |

| Desires/Aspirations/Goals | – I want my own apartment so I can have people over – I want to be able to get a car so I can get to more places easily – I want to get a job working with animals – I want to learn how to play the guitar because I enjoy music |

| Capabilities | – I am able to take my dog on a walk each day – I am able to work a part-time job that allows me to pay my bills – I am able to cook meals that connect me to my culture – I am able to take the bus to get to my medical appointments |

| Useful or Helpful Environmental Strengths | – My brother has a car and is willing to take me places I need to go – Walking on the trails close to my house helps me get exercise and connect to nature – Listening to jazz helps center me and feel calmer and content – Caring for my cat gives me a sense of purpose and responsibility each day |

Creating space to notice anything in the above areas can be a challenging task, especially if we are feeling overwhelmed when a person is presenting with intense emotions, distress, or life challenges. We can be tempted to move too quickly into problem-solving or trying to “fix it” (also known as the righting reflex).

Spending time using empathic communication and employing our noticing behaviors doesn’t mean we are ignoring people’s problems, barriers, or challenges. Instead, it allows us to have more information in which we can consider options, target specific tangible supports we can offer, and make more informed decisions.

Ultimately, what we notice will impact our approach and the interventions we use. If what we notice centers primarily on the problem, barriers, and challenges people experience, then our approaches and interventions will be primarily geared toward helping people resolve problems.

Yet, if we expand our capacity to notice things in the areas mentioned in Table 2, then we lay a foundation for our approaches and interventions to revolve around helping people make movement toward things they value or want in life, even amid the problems, barriers, or challenges they experience. This helps to open an avenue of hope. And what we notice will help us identify a context in which we will be able to introduce the first primary tool of SMCM – the Strengths Assessment and enter into the second phase of the model – Invitation to Explore.

Phase 2: Invitation to Explore

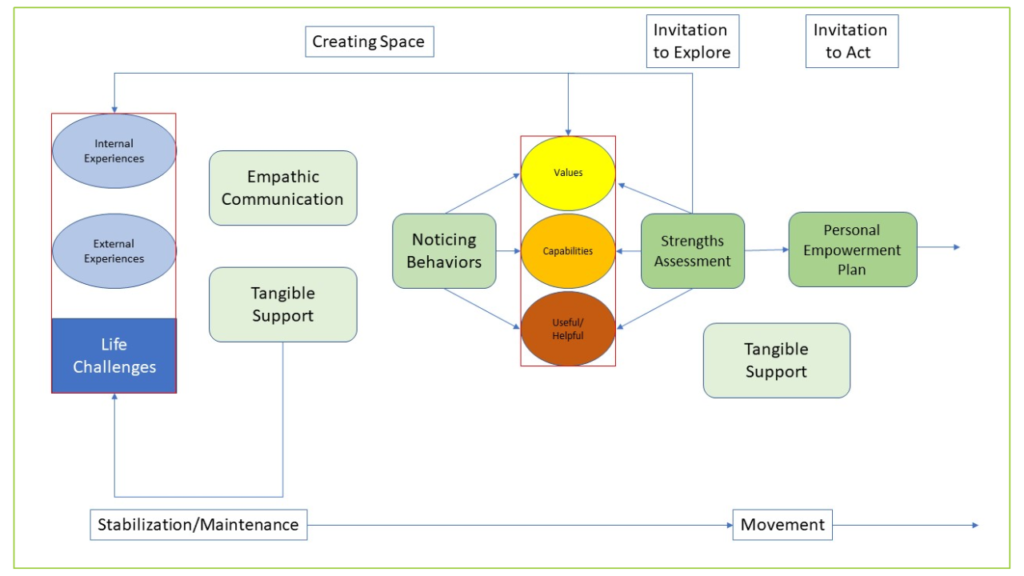

In phase 1 of SMCM, we discussed our active efforts to notice what people value, their desires and aspirations, current capabilities, and what they report as helpful or useful. In phase 2 of SMCM, our goal is to intentionally create space between any of these things and the internal or external life challenges the person experiences.

This is the primary purpose of using a Strengths Assessment – to visually allow a person to see that what they value and want in life (desires and aspirations), what they are currently able to do (capabilities), and what they find useful and helpful in life (environmental strengths) exist independently from what they are experiencing inside of themselves and the world around them.

This does not mean that these things are not impacted by what they experience internally or externally. It just means these things have a substantive reality in their own right. Here is an example. A person might desire to get a job because they want to have enough money to get an apartment and also because it gives them purpose in life.

They might be worried about getting a job because they experience anxiety when they are around other people. In this example, social anxiety can impact a person taking steps toward employment AND they want to get a job for all those reasons mentioned above. Those values, desires, and aspirations exist whether or not they experience internal distress.

Figure 6. Phase 2 – Invitation to Explore

This phase of SMCM is called an Invitation to Explore because it doesn’t require the person to take any steps toward anything they value or want in life. It doesn’t require them to make any life changes. Introducing a Strengths Assessment is an invitation to explore possibilities. All you need to introduce the Strengths Assessment tool is a context. Table 3 shows various contexts in which you can introduce a Strengths Assessment.

Table 3. Contexts to Introduce a Strengths Assessment

| Context | How it might sound in practice |

| A goal a person wants to achieve | “I know it is difficult seeing yourself working right now, considering how uncomfortable it feels being around other people, AND it sounds like getting a job is important to you because you would like to earn enough money to get an apartment. You also mentioned when you have worked in the past it has helped provide structure and a sense of purpose. I wonder if it is worth exploring what it might take for you to be able to work again.” |

| A symptom that is challenging or distressing to a person | “It sounds like hearing intrusive voices makes it difficult to get through each day and for you to be able to do things you want to do. Would it be helpful if we took some time to look at some of the things you would like to be able to do if the voices were less intrusive?” |

| A behavior change a person wants to make | “Stopping or reducing alcohol seems frightening just thinking about it. AND it sounds like you see that as being a pathway to rebuilding relationships with important family members. Is it worth exploring what support you might need if you do decide you want to take a step toward sobriety?” |

| A value a person holds | “Everything you are saying tells me how important family is to you, especially your desire to be a supportive father to your son. Is it worth looking at some of the things you are already doing related to this and maybe exploring other things that might help you continue moving in this direction?” |

| The person doesn’t know what they want | “Right now, things are very overwhelming, and you are not sure how I can be helpful to you. Would it be okay if I showed you a tool that might help us explore some things that are important to you? Maybe then we might be able to identify some ways I could be helpful.” |

For the purposes of this conceptual framework, you have moved to Phase 2 of SMCM when you record anything on a Strengths Assessment. Starting a Strengths Assessment can be as simple as recording a few values, desires, or aspirations that are important to a person, a few things the person is able to do even amid current challenges (capabilities), or a few things that are useful or helpful to a person related to something meaningful or important or a life challenge.

Nothing in Strengths Model practice is linear; therefore, entering into Phase 2 does not mean we stop doing key processes used in Phase 1 (i.e., empathic communication, employing noticing behaviors, and offering tangible support). We are continuously trying to engage with people and build a working alliance throughout the helping relationship.

Phase 2 adds depth and substance to how we listen to people and creates a mechanism that brings focus and intentionality to how we provide support to people. It sets the stage for creating opportunities to move toward value-based action rather than continuously reacting to internal and external stressors that perpetuate the unhelpful loop.

While Strengths Assessments can typically be started with a person within the first 30 days of the initial meeting with a person, there are no rigid time frames on when you HAVE to introduce a Strengths Assessment. If you are not able to introduce the Strengths Assessment in the first 30 days, then you should continuously be looking for opportunities to introduce the Strengths Assessment in a context that is relevant and meaningful to the person.

A good Strengths Assessment starts slowly and evolves over time. There should never be a rush to record something in every box (blank boxes are okay). One intent of starting and building upon a Strengths Assessment over time is to help us eventually find a value or goal that a person is willing to act on (Phase 3).

Phase 3: Invitation to Act

Supporting people in taking values-based action steps toward something that is meaningful and important to them is a hallmark of Phase 3 of SMCM. Therefore, introducing the Personal Empowerment Plan (PEP) is an “invitation to act.” There is no set timeline for moving from starting a Strengths Assessment to starting a PEP. Some people might be ready to start taking steps toward a goal after writing a few desires or aspirations on a Strengths Assessment. For others, they might feel overwhelmed or unsure of what they want, and it might take several meetings before they can identify something they specifically want to work towards.

Figure 7. Phase 3 – Invitation to Act

As with the Strengths Assessment, you do not want to introduce a Personal Empowerment Plan unless there is a context that is relevant or meaningful to the person in which to use the tool.

Table 4. Contexts to Introduce the Personal Empowerment Plan

| Context | How it might sound in practice |

| A goal a person wants to achieve | “It sounds like you want to get a job and it feels overwhelming thinking about where to start. I want to show you a tool I use to help this feel a little less overwhelming. We don’t need to think about everything that needs to be done to get a job, just a next step to help us get started.” |

| A symptom that is challenging or distressing to a person | “I know the anxiety you experience makes it difficult to be around other people, and you have mentioned how important it is to you to be connected to people. I want to show you a tool that might help us slowly and mindfully explore some initial steps to get started.” |

| A behavior change a person wants to make | “It sounds like you are at a point where you are considering making a change related to alcohol. I know this is a big decision for you and feels frightening. I want to show you a tool that will help you stay in the driver’s seat of your decisions and allow me to be a support for you each step of the way.” |

| A value a person holds | “You have been taking a lot of steps to take care of your health and wellness. I also hear your worry about staying connected to your children while you are trying to focus on yourself right now. I want to show you a tool that might help you continue the work you are putting into yourself AND see the efforts you are taking to invest in your relationship with your children.” |

You do not need a PEP for every goal a person has while receiving services. The important thing is developing a focal point where people can visually see that they are moving toward something. The intersection of Phase 2 and 3 in SMCM differentiates this model from any other case management approach.

Most case management approaches are highly reactive, transactional, and problem-driven. When we do not bring focus to interventions tied to relevant life areas that are important to people, then by default, we are setting up a helping relationship where we end up waiting for problems to arise and then trying to fix them. The unintended consequence of this is that we end up joining people in the unhelpful loop described in Figure 3. and reinforcing it, rather than offering a potential pathway to continue making movement in areas where people find value, meaning, and importance.

The PEP is a means of helping people mindfully take values-based, committed action through small, measurable steps. The visual format of the PEP, as well as the Strengths Assessment, allows us to clear enough mental headspace (which occupies our worries, doubts, fears, etc.) to focus on a potential, doable action in front of us.

The iterative nature of the PEP allows us to test a step and use the information gleaned from that step to formulate the next one. When steps produce the desired movement toward something a person desires to achieve, then we have the opportunity to acknowledge and reinforce agency and capability, even amid challenges. When steps do not produce the desired movement, we have the opportunity to acknowledge effort and recalibrate our approach or pursue alternate strategies.

Phase 4: Establishing and Strengthening Anchors

Phase 4 is characterized by helping people see that their lives are more than the problems, barriers, and life challenges that brought them into services. While some of this started when you introduced the Strengths Assessment in Phase 2, there is a renewed focus here after we have made some initial progress in a few life areas. We use the Strengths Assessment to help people visually see that the efforts they are making while in services are building toward something.

The boxes on the Strengths Assessment have limited space, which is intentional. The goal of evolving a Strengths Assessment isn’t to capture every strength a person possesses. It is to bring to focus the key strengths that are contributing to the movement the person desires. A person should be able to look at their Strengths Assessment at various points while receiving services and see very clearly key values they hold, aspirations they desire to move toward, capabilities that acknowledge effort, and the useful/helpful things they have incorporated into their life. Building out a Strengths Assessment isn’t about quantity.

It is about quality, relevancy, and meaningfulness. It’s about helping people see that they are building a foundation of anchors that will allow them to navigate present and future life challenges. It’s about helping people continuously see that who they are is more than a diagnosis they have received, symptoms they may experience, life traumas, addiction, or anything that may have obscured their view of themselves as a person of value, worth, and potential.

Here are some possible areas that you could focus on to emphasize the anchors that people are developing while in services:

- A goal a person has achieved that was initially a future aspiration

- Something a person is now engaged in that they weren’t previously

- Something a person is now able to do that they weren’t previously

- Something a person has incorporated into their life that is useful or helpful to them

- People who are particularly useful or helpful to the person

- Naturally occurring resources that have replaced or supplemented support that was previously only provided through formal services

- New desires or aspirations the person is now considering

Adding things to the Strengths Assessment might also mean removing other things. It could be a reflection that some things have changed or are no longer as important as they used to be, or that new strengths that have been identified hold more power, weight, or relevancy to the person than some that were previously recorded. Mostly importantly, the information on the Strengths Assessment should reflect movement and growth in areas that are meaningful and important to the person.

Another important aspect of Phase 4 is continuously refining the focal point of services that we are providing/coordinating for the person and our particular role of support. It can be tempting, once we find an initial focal point within Phases 2 and 3, to loosen up our approach and just focus on the primary goal we are working on. If we are not careful, we can end up right back in a reactive, transactional approach to case management.

Phase 4 allows us to continuously evaluate where we are at from month to month in the overall plan of care and refine our efforts to specifically target the areas where the person most needs our support. Reactive and problem-based approaches to case management leave the worker vulnerable to continuously extending their tenacles of support while remaining perpetually in a stabilization/maintenance mode of service delivery. SMCM seeks to visually consolidate gains in self-directed action, enhanced capabilities, and acquired useful/helpful personal and environmental strengths via the Strengths Assessment and visually focus on efforts being taken to make movement in areas where support is still needed via the Personal Empowerment Plan.

Phase 5: Graduated disengagement

While we refer to graduated disengagement as a distinct phase in SMCM, it actually begins to take shape in the early engagement periods with a person and continues throughout all the phases. Early on in engagement, the SMCM practitioner is finding ways to understand from the person’s perspective what an end to services might look like and what would constitute measures of improvement if services and supports were successful.

While many people will not be able to explicitly convey that to the worker outright, the layout of SMCM practice provides multiple ways for the worker to engage the client in a process of exploration, identification, and clarification of what they value and want in life. While this does not mean the worker is responsible for making everything the person wants a reality, it is through these discussions that the worker and client begin to negotiate together how the services and supports offered through the organization might be able to support the person in their continued efforts to build or rebuild the life they are pursuing.

It’s the difference between a worker jumping feet first into a situation and immediately swatting at each problem and challenge as they arise and taking the time to sit side by side with a person to collaboratively begin constructing and evolving a client-centered, goal-focused plan. Problems, barriers, and challenges will be encountered regardless of the approach.

That is the nature of life. The latter approach at least allows the worker and client to place problems, barriers, and challenges in the context of how they impact (or have impacted) valued life areas, goals, and aspirations held by the person. It sets up a process where the worker and client can try different things and evaluate if what they are doing is helping the person move in the direction they want to go. It sets up a process where the worker and client can acknowledge and celebrate progress in self-directed action, learning, and new ways of responding to and navigating life challenges.

Where SMCM most clearly enters Phase 5 is when we begin concrete and transparent discussions with a person about ensuring a smooth transition out of case management services or to a lower level of care. It is here that using the Strengths Assessment can again be helpful. A well-done Strengths Assessment, evolved slowly over a person’s time in services, will not only show progress; it will also allow you to acknowledge that the person still has goals and aspirations they are moving toward.

For some people, they will be able to continue their life journey with support from the naturally occurring resources that surround them. Others may need to be connected to other services that can support them in specific areas. Using the PEP one final time can be helpful in making those warm handoffs to other services.

Transitions are difficult for both workers and people receiving services. Using an intentional, purposeful, goal-focused approach like SMCM increases the likelihood that the transition will be viewed as something to celebrate. This is because it is not only an acknowledgment of goals that have been achieved in services but also a validation of the person’s sense of empowerment, autonomy, and agency. SMCM does not mean that a person will not experience future problems, barriers, or challenges in life. What it will mean, if successful, is that the person will be in a better place to navigate those challenges than before they entered services.